Convention Presentation

by Shirley Smith

June 17, 2004

(Editor’s Note: The following article is a condensed version of the wonderful talk Shirley gave the NMGCS Convention on Thursday, June 17, 2004. It should give us all food for thought! If you have any information for Shirley you can contact her at ![]() )

)

Also see the convention pictures, and download a copy of the presentation materials in PDF fomat.

- Times change

- Technology changes

- You really must question old ways

The goal in my presentation today is to show how these guidelines must be followed in studying a glass collection.

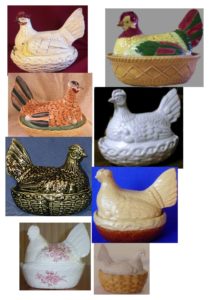

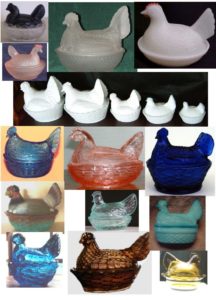

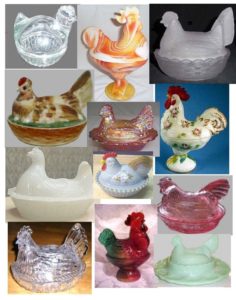

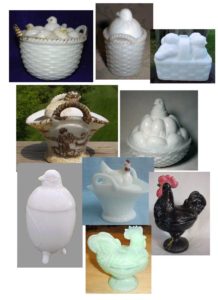

I collect glass hen on nest covered dishes – and ONLY hen on nest covered dishes. I don’t know why; I just do.

One thing that complicates their study is the fact that, unlike other glass objects, they may be referred to by many names. There are at least 50 different names for a hen on nest dish…from “animal dish” to “trinket box.”

All this means you must make a mental note to watch for these terms. As far as I can discover, Westmoreland first used the term “hen on a nest” back in the 1930’s and subsequent authors shortened it to “hen on nest,” which is commonly used today.

A Little History

Covered porcelain dishes representing animals originated in China several hundred years ago, and were later made in Europe. Dishes made by Staffordshire and Dresden were popular in America from about 1790-1820 but were quite expensive.

Ivo Haanstra, in his Glass Fact File A-Z, tells us that hen on nest pressed glass animal dishes made their first appearance in Germany about 1895. Perhaps they did make their first appearance in Germany that late but they certainly were made, at least in the United States, earlier than that.

Perhaps as early as the 1860s, several glass factories began making a covered dish in the form of a hen on a nest. These cheaper copies of the more expensive European ceramic hen dishes proved to be extremely popular. It was commonly made in 5-and 7-inch sizes.

The glass hen dishes were all pressed glass, which means they could not have been made before 1828.

Most of them are non-flint glass which means they were made after 1864 or so. I have not been able to verify if any glass hen on nest dishes were made of lead glass prior to 1900.

Looking at the American companies that were in business in the period 1860-1880 and known to have made hen on nest dishes, we have Atterbury, Challinor, Sandwich, Central, and McKee.

Atterbury and Challinor are pretty much documented as to production of glass hen dishes in the late 1880s.

McKee is not known to have made their hen dishes prior to the great mustard container craze of the late 1890s.

So, that leaves Sandwich and Central as possible makers of the first hen on nest covered dish. Central is thought to have made their hen dishes, most of which were frosted, about 1875 or so, which would coincide with the widespread use of acid etching of complete pieces. When Sandwich first made their hen dishes is anybody’s guess, but it would have to have been before they went out of business in 1888.

As far as when European glass companies may have first produced glass hen on nest dishes, it is any body’s guess at this point.

So far I have identified 50 companies known to have made hen on nest dishes with another 40 companies possible. I have identified 191 different sizes or forms and I am sure that is not the end of it. A new one seems to pop up at least once a week – especially those which cannot be attributed to any known company.

Other than the United States, glass hen on nest dishes are known to have been made in the countries of England, the Czech Republic, Poland, Germany, Finland, France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan. That probably is not the end of that list either!

Glass hen on nest covered dishes have been made in sizes ranging from less than 2 inches to 8 inches in length.

They have been made in every color from milk glass to black glass, and in a variety of finishes including frosting, iridizing, fired-on painting, staining, and hand painting. They have also been made in 24% lead crystal.

In my collecting, I also include variant forms of hen on nest dishes such as various standing roosters, and chicks coming out of eggs.

RESEARCHING AND DOCUMENTING

Now, let’s get down to the nitty-gritty of studying your glass collection. In the introduction to their book, Yesterday’s Milk Glass Today, the Ferson’s state, “The lure of collecting lies not just in the finding but in finding out about each individual discovery.” Some collectors do this to authenticate pieces for monetary value; others do it just because they want to know.

Although I will be talking about my collection of glass hen dishes and using illustrations of covered hen dishes, I think that the basic procedures of this process of “finding out” apply to any glass form that you might collect.

There is a list of research problems that underlies all the studying about glass that we do:

1. Factory information as to dates of production, items made, catalogs, and various name changes and ownership transfer is very “iffy.” Old factories, and most newer ones, simply didn’t bother to keep records. They were interested in turning out as many, varied items as quickly as possible to turn a profit. Also companies came and went, burned down, rebuilt and changed their name, went bankrupt, reorganized, joined combines, merged, or simply disappeared.

2. Moulds are a problem and no one has had the courage to address their history. A mould maker may have made very similar moulds for different companies, moulds may have been copied or duplicated, moulds may have been transferred from one company to another, they may have been borrowed, lent, modified, sold as auction several times, sent abroad and returned here. Another problem with moulds is that the original company’s mark may be used on moulds sold and used by another company, such as the case with the Westmoreland moulds used by Rosso and Summit.

3. Myths – repeated as fact over and over are major problems. For example, the story of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree. This story is told in school. We all have heard it. We believe it. But the story is pure fantasy made up by Mason Locke Weems, in his 1800 biography of Washington to show Washington’s fortitude of character.

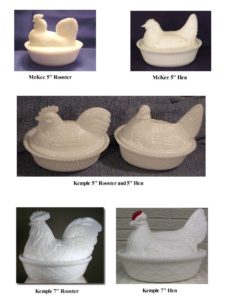

To bring this closer to home, let us consider the four Kemple hen on nest covered dishes. These were said by Mr. Kemple and his wife to be made from original McKee moulds. They are listed that way in Burkholder’s book on Kemple, they are listed that way where they are cataloged and stored at Wheaton. My inquiry to Gay LeCleire Taylor at the Museum of American Glass resulted in the firm statement that the moulds were McKee moulds.

It looks possible that Mr. Kemple could have had a 5” McKee split rib base mould – but even that is debatable. Looking at the only documented McKee rooster and hen, and at the 4 Kemple glass hen on nest dishes, it rather stretches one’s imagination and common sense that the Kemple items were made from original McKee moulds.

Still other often repeated stories which I consider rather romantic myths are those of the itinerant glass workers who took moulds with them from one place to another, and slag (marble) glass being produced by pouring leftover glass into one pot at the end of the day. It is highly unlikely that glass workers, even if they stole some expensive moulds, would be able to drag the heavy things around the country. It is also technically impossible to pour different formulas of glass together at random.

Keeping these three hindrances in mind – lack of factory information, the story of moulds, and myths, let’s look closer at the basic tools of studying one’s collection:

These are:

- Observation

- Reading

- Communicating with other collectors

- Computer-based information

These aren’t quite as simple as they look. Let’s look at these tools a little more closely.

OBSERVATION

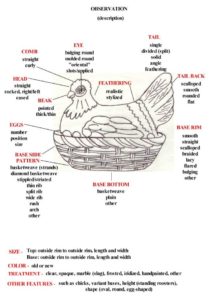

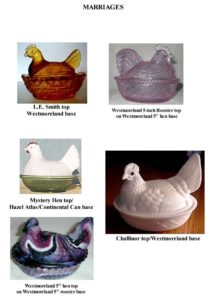

Remember that in studying hen on nest covered dishes that there are two pieces involved and each must be observed closely for correct attribution and to avoid the problem of a “marriage” of a top with an incorrect base.

1. LOOK at it. Really look at it. Careful observation can reveal many things.

2. OBSERVE the size – exact measuring is important. I measure both the top and the base from outside rim to outside rim. Although there may be a slight variation in these measurements due to the glass being hand pressed, it usually isn’t enough to confuse attribution. You will learn such things as a Challinor hen top won’t fit on an Atterbury base; it is a tad too large.

3. OBSERVE the color and/or type of glass – frosted, slag, oily feel, dead white milk glass or opalescent. It is important to know original colors from newer ones. Original Westmoreland 5-inch hens were not made in carnival; most of their carnival hen dishes were made for Levay in the 1970s and early 1980s.

4. OBSERVE the overall form including the base – marriages, that is a mismatch of top and base, are certainly possible.

5. OBSERVE distinguishing features On close study, it will be found that most hen dishes have some sort of distinguishing feature that sets them apart from other hen dishes.

6. OBSERVE Marks Atterbury never used their patent date on any hen on nest dish except for the Chick on Eggpile. Sowerby had a mould mark for many items but it has not been seen on their hen dish. Many companies did not mark their hen dishes, such as Indiana, Wright, and Central. Many companies may or may not have marked their hen dishes such as Degenhart, Fenton, and Westmoreland. Companies may also have changed their mark over time such as Boyd, Fenton, and Westmoreland.

Labels are another story, which I won’t go into here. You must realize, though, that labels can be switched to items that they were never meant to identify.

The second item on our list of research tools is READING

We are talking research here and that entails a whole different kind of reading.

Hundreds of books on glassware have been published in the past 50 years. This availability of information makes it easier for collectors to identify pieces. Nevertheless, major problems still exist in authenticating glass. While books are quite helpful, they do contain mistakes and sometimes contradict each other.

In doing research, one must beware of “wishful reading,” that is, seeing what you want to see. If you are determined to prove that Central Glass Co. made the Fenton prototype arched base hen, you can certainly read into some writings that this might be so.

It is well to approach all reading without preconceived notions or a desire to prove something. One must challenge conventional wisdom, reconsider that which you believe to be true, and think for yourself. This last is hard to do. It is sooooo much easier to just accept things.

1. Types of materials:

a. Primary source materials: these include original papers such as birth & death certificates, deeds, city directories, company catalogs, company business records, photographs, patents, manufacturing directories, newspaper articles, and trade journal articles such as appear in American Pottery & Glass Reporter, Crockery and Glass Journal, or China, Glass & Lamps, Many authors have spent countless hours in searching out and documenting these primary sources. We owe them a deep debt of gratitude.

b. Secondary source materials: these are printed materials which were written based on primary source materials as well as information from other sources. These may include books, exhibit collection brochures, magazine articles such as those in Glass Review and Glass Collector’s Digest, and collector club publications such as Opaque News.

It’s in these secondary sources that the problems of hearsay, opinions and speculation comes into play and where you must be most cautious.

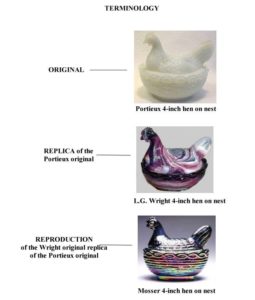

2. Terminology. In reading, we must be aware of terminology and how it is used. There doesn’t seem to be standard definitions of many terms used. For example, “crystal” may mean clear glass or lead glass; “flint glass” may mean lead glass or non-lead glass, “antique” may mean anything older than the writer; “vintage” may mean anything at all; “original” may mean only those items produced in the 19th century; “reproduction” and “reissue,” “replica,” “fake,” “imitation,” and “copy” seem to be used interchangeably.

This is an area that that I feel has stymied the study and documentation of glass collecting since the 1920s. Although “reproductions” were mentioned in the literature early in the 1920s, it took Ruth Webb Lee in her book, Antique Fakes & Reproductions, first published in 1938, to really stir things with a stick and set the tone of collecting for years to come. Nowhere in her book did she define “reproduction,” and nowhere did she say what the items were a reproduction of. Close reading of the book shows that no distinction was made between a “reproduction,” a “reissue,” or an entirely new item that was merely similar in form to another item.

Dorothy Hammond, in her book, Confusing Collectibles, A Guide to the Identification of Reproductions, first published in 1969, starts out with definitions on page 6.

“A ‘reproduction’ is a ‘likeness.”

“To ‘reproduce’ means to ‘cause to exist again.”

“Reissue’ is to ‘issue again.”

“Fake’ is to ‘impart a false likeness”

What do these dictionary definitions mean in glass collecting? Not much. They only tend to muddy the waters, especially when none of the rest of Miss Hammond’s book uses these definitions in what amounts to merely listing items that the author cannot identify.

Both Lee and Hammond tiptoe around the implication that they assume that collectors only want old originals because of their monetary value. It is the buyer’s or collector’s responsibility to know what is being sold and what he or she wants to purchase. It is unfair and rather naïve to blame someone else for your lack of knowledge. In studying one’s collection, and correctly attributing a piece (for whatever reason), one must use terms precisely and one must do their homework. “To know the old, you must know what is new.” One must also keep in mind that one hen on nest form pretty much looks like another.

So, to facilitate my collecting, I use various terms in very specific ways. I am not asking you to use the terms in this manner. I just want to show you how I use these terms to help me specifically identify a piece in my collection. If nothing else, I would like you to think about what the terms mean to you when you read them.

1. Original = an item produced by a company from a mould they either made themselves or had made for them in the company’s own unique design [EG. Atterbury, Smith, Avon, Central, Sandwich, Vallerysthal, Indiana]

2. Reissue = an original item made by the original company over a period of time [EG.-Westmoreland, Imperial, Fenton] If the older pieces are what you want, you must know their characteristics as well as the characteristics of the newer pieces.

3. Reproduction = an item produced by a company who acquired the original mould from another company. The mould may have been transferred through previous companies. [EG. Boyd, Rosso, Mosser, Summit] Reproductions can usually be distinguished by color. Original mould owner’s marks may remain.

4. Replica (copy, imitation, facsimile) = a piece produced from a new mould that resembles an original item from another company. Usually minor differences and color facilitate attribution.

I do not think there is such a thing as a “fake.”

Let me explain all this with an example.

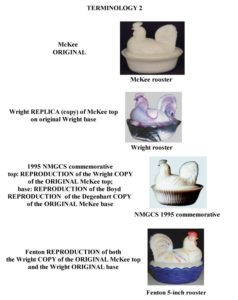

Take the Wright 5” rooster covered dish, an L. G. Wright 5” rooster, the NMGCS commemorative, and the Fenton 5” rooster covered dish.

The Wright 5” rooster top is a copy of the McKee original 5” rooster top. The base for the Wright dish is an original Wright mould.

The NMGCS commemorative is made up of a top which is a reproduction of the Wright copy of the original McKee top. The base is a reproduction of the Boyd reproduction of the Degenhart copy of the original McKee base mould.

The Fenton 5” rooster on nest covered dish is a reproduction of both the Wright copy of the original McKee top, and the Wright original base.

Complicated? Perhaps. But, to really know your collection, or what it is you want to collect, you must go through this process. It is not enough to just say that everything that you are unfamiliar with is a “reproduction.” It doesn’t mean anything; and it doesn’t tell you anything.

In this way, you can definitely identify and attribute a piece. Now, whether or not this is what you want for your collection is another matter.

3. Having mentioned types of materials and terminology, there is one more reading technique we must note: critical reading and analyzing what you read.

People read in a variety of ways for a variety of purposes. You can read a novel for entertainment, you can read a recipe to prepare food, you can read a nursery rhyme to children, and you can scan the newspaper. The goals of critical reading require that you:

- Recognize the author’s purpose

- Understand the tone and persuasive elements

- Recognize bias

Critical reading is not simply close and careful reading. To read critically, one must actively recognize and analyze evidence on the page by being rational, aware of one’s own biases, and stay open-minded. Critical readers are skeptical and active thinkers.

To be critical readers, we must note the following:

a. What are the author’s credentials: Is the author a noted authority? What do reviewers say about the author’s writings? We can benefit from the proven and accepted accumulated wisdom of such writers as: Ruth Webb Lee, S.T. Millard, E. McCamly Belknap, Everett Grist, the Fersons, Anne Cook, Frank Chiarenza, James Slater, Faye Crider, Francis Price, Ruth Ann Grizel, Raymond Notley, Lorraine Kovar, Charles Wilson, Joseph Morin, Debbie Coe, Red Roetteis, Albert Christian Revi, Arthur G. Peterson, the Welkers, Tom Felt, James Measell, the Garrisons, William Heacock, Tom Klopp, Joseph Morin, the Newbounds, Rush Pinkston, the Sanfords, Helen Storey, the Thistlewoods, and John Walk. All are noted authorities. But, even these authors must be read critically. Please note how many of these writers are or were members of our society.

b. Are there citations and references? Is there a bibliography? This authenticates and lends credence to what is written. Ruth Webb Lee, expert that she was, never included any footnotes, citations, or references and we are left to wonder just where her information came from and how believable it is. John and Elizabeth Welker, on the other hand, were meticulous in referencing their information.

c. Is the author’s writing logical? One can spend an entire semester at college studying logic, but I think that most adults can recognize something that is not reasonable.

Take this example: “Henry Ford made a lot of cars and they were all black. I have a black car. It must be a Ford.” Is the conclusion, that I have a Ford, logical? No….because there is missing information in this example…other manufacturers made black cars.

Or, take this example closer to home: “Fenton and Imperial made a lot of glass items in the hobnail pattern. Both Fenton and Imperial made hen on nest covered dishes. I have a hen on nest dish that has hobnails around the rim of the base. Therefore, it must have been made by either Fenton or Imperial.” Does the conclusion follow from the statements? No, other companies made items in the hobnail pattern, and we have no statement that Fenton and Imperial made hen on nest dishes in the hobnail pattern.

To simplify it….if you read something and your inner voice says, “That doesn’t make sense,” it is probably not logical.

d. Does the author separate opinions, speculation and hearsay from facts –

“It appears to be a Westmoreland product…” (speculation)

“Perhaps it was produced in other colors also.” (speculation)

“Old glass is finer than new glass” (opinion)

“The seller told me that the company didn’t make many of that piece.” (hearsay)

“A 1930 catalog page shows the item listed as #1-covered hen dish.” (fact)

“It is a beautiful piece.” (opinion)

e. Is the writer being subjective (that is, speaking from a personal point of view) as in “Of all the Tree of Life interpretations, I consider the Portland at once the earliest and the best in quality.” or objective (that is, speaking without personal comment or interpretation) as in “The Portland Glass Co., was founded in Portland, Maine, in November of 1863.”

I know that all this is becoming tedious. But, hopefully, it will give you something to think about next time you read an article or book on glass.

We have gone over the basic research tools of Observation and Reading, and I want to quickly go over the 3 tools that are left.

COMMUNICATING WITH OTHERS

Perhaps the most valuable tool in gathering information is in discussing and sharing information with others. Information exchanged may include new observations, new print sources, and new conclusions.

This can be done, nowadays, in a variety of ways:

- By mail, e-mail, e-lists, meetings, collector group meetings, conventions, telephone

- Writing existing glass companies (lots of luck!)

COMPUTER-BASED INFORMATION

The Internet has had more of an impact on society and the individual than the invention of the Gutenberg press. It presents access to billions of pages of information to anyone at any time. It also offers instant communication. It is, of course, not to be ignored by any collector.

1. e-mail – if you are on-line, you don’t need me to describe how useful e-mail is. You can use it to contact companies and authors as well as other collectors. And if you aren’t on-line, you are missing one of the most astounding and delightful and magical tools of the modern era.

2. e-lists, forums, message boards – an e-list (electronic list, listserv) is a way to communicate with a number of people, perhaps worldwide, and to see what others write and reply. These are almost always on a particular subject or interest area. Forums are Internet sites where users can post questions or answers in real-time. That is, several people can talk back and forth to one another at the same time. A message board is similar to e-lists and forums – members post a question and other members can answer. All members can see the questions and answers. The difference between a message board and an e-list is that e-list members are e-mailed postings, but on a message board, a member must log onto the site to see postings.

And, I do wish our Society’s Web site had one of these features.

3. Web sites, personal and commercial, can offer much text and pictures. These are listed when you do a search on your subject area in a search engine such as Google. There are Web sites for glass collecting in general; for specific glass collecting clubs; for glass companies such as Fenton, Westmoreland, Fostoria, etc.; for types of glass such as, milk glass, carnival glass, and Czech glass; for forms of glass such as flower frogs and rose bowls.

There are also Web sites which offer links to other Web sites that help with research such as the national American Glass Club Web site and our own NMGCS Web site.

4. Auctions – not only can on-line auctions offer you items that you collect, they can also give you the wrong photograph, the wrong measurements, the wrong attribution, and a long, unbelievable tale of provenance. But auctions can also give valuable information for your collecting research: showing original packaging, labels, colors, and new items.

Don’t miss Froogle, a shopping division of the Google search engine. You can find a link to it on the Google home page. Froogle lists auctions and sales worldwide. You can do a search on your area of interest.

5. Translations – If you are really serious about researching your collection, you will inevitably run into resources in foreign languages. Some of these offer an English translation; others don’t. But you can translate French, German, Italian, Spanish, or Portuguese at the Google search engine using their translation tool. If you type in a Web site address, the whole page will be translated when you are taken there. You can also just type in text you want translated.

6. CDs. In this rapidly growing age of technology, a lot data is stored on CDs which can be accessed from your computer. One such goldmine of information is the Indiana Glass Company CD from Donna Adler’s Web site. It contains not only pictures of glass, but a chronology of the company and 36 pages of company catalogs. For $12, it is much cheaper than a book! Hopefully, we will see more and more information distributed this way.

So there you have it…..the techniques for analyzing and studying your collection:

To review the process of studying your glass collection:

- You must be passionate and determined about it.

- You must be observant and describe findings accurately.

- You must read critically.

- You must be open-minded and willing to change.

- You must avoid wishful thinking.

- You must be aware of opinions, speculations and inferences with incomplete references.

- You must acquire print materials, as well as utilize computer-based information.

- You must discuss with others.

- You must review everything again…and again.

- Times change

- Technology changes

- You really must question old ways